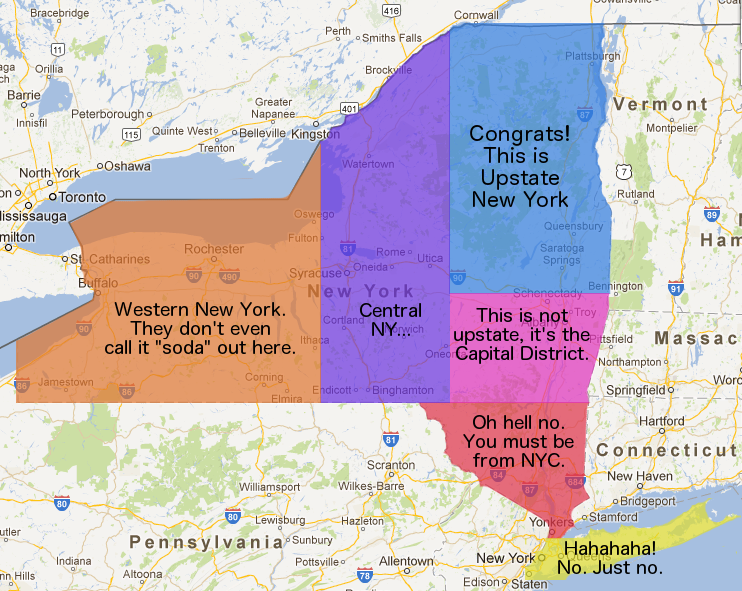

Locality Matters

Procedures for buying and selling real estate can vary significantly depending where you are in New York State. Some differences are a result of local laws, others are a matter of local custom. For instance, in some parts of NYS it is routine for real estate agents to prepare the real estate sale contract and hold the buyer’s deposit. In other parts of the State, these tasks are performed by attorneys. Attorneys are likely to play a more prominent role in urban and suburban areas where property values are higher, but this is only a broad generalization. Practices tend to be more uniform within the same county, but even here there are notable exceptions. There are requirements for transferring real property in New York City that are not followed in the rest of the State. In rural parts of the State, it is not unusual for property deeds to address issues such as private road maintenance and shared access to bodies of water. For these and other reasons, it is useful to consult a professional in the local area where a property is located to know what to expect before embarking on the process.

Title Companies play an essential role

Title companies insure the interests of buyers, and in many cases also their lenders, by guaranteeing financial compensation in the event a problem with ownership of real property arises after the transaction has closed. The attorney for the buyer is usually the party that orders a title search once a real property sale contract is signed. In order to assess possible risks relating to title, title agents conduct a detailed search of public records to determine, as much as possible, if the seller has all rights to convey clean title to that property. They present their findings to the parties in a detailed report. But the information in the public records cannot be relied on absolutely. There is always the small risk that information is missing, inaccurate or fraudulently entered for instance. Title insurance protects innocent parties from these kinds of risks to ownership of a property. The title agent also clarifies the types and amounts of taxes and other charges relating to a piece of real property, and if an intended seller is up to date on these charges. If not, the amount of arrears that need to be settled as part of closing for clean title to be conveyed is determined and assured by the calculations presented in the title report. Title agents are typically present at real estate closings, and among other tasks record a notarized copy of the deed with the county clerk.

Knowing your boundaries

Prospective buyers typically walk the perimeter of a property being offered to them. They may well wonder if the apparent borders are correct and if a surveyor should ensure the dimensions of the property and its boundaries. Whether or not to order a survey is a case by case judgment call. While property lines are important, and disputes between neighbors over their exact borders are unfortunately common, that does not mean a survey is always advisable prior to purchase. Incidentally, title insurance will usually not pay claims based on small irregularities in the exact size or boundaries of a piece of property. And yet, most purchases occur without a new survey. This is mainly because surveys are relatively expensive. The boundary description provided in the most recent deed to a property is often clear enough to make the cost of a new survey outweigh any likely benefit. However if a buyer has very specific plans, for instance to build on a site where the intended new building is going to be near a boundary, then a new survey might be advisable to ensure the property can be used for the buyer’s intended purpose.

Cash is not necessarily King

Expect particular rules to apply to the forms of payment permitted for buying real estate. While “all cash deals” are not uncommon, this does not imply buyers appearing at the closing table with a bag full of currency. While this does happen, and is not illegal, it should be noted that any transaction involving more than $10,000 Dollars in physical currency requires a CTR (currency transaction report) to be filed with the U.S. Treasury Department. Rather, “cash deals” are those being done by buyers who do not need to borrow from a bank or other lender by mortgaging the property purchased. Pay close attention to the payment terms in your contract. Most real estate contracts specify a much lower permissible limit for partial payment at closing with physical currency or personal checks, most commonly $1000. Other closing funds are typically required to be presented in official bank checks or attorney escrow checks. This serves to minimize the risk of parties having to accept and transport large amounts of cash, or of a check being dishonored after title to a property has passed. Incidentally, bank checks are typically not required for making down payments. Personal checks are most commonly used for this purpose. This is because there is adequate time for the personal check to be cleared into the escrow holder’s account. There is no real risk in such case if a buyers deposit check is dishonored, since title to the property is not yet at stake.

The Property Condition Disclosure Statement (PCDS) in New York

Since 2002, most sellers of residential real property with 4 or fewer dwelling units are required to provide potential purchasers with a PCDS in statutorily prescribed form prior to signing a binding contract of sale. The PCDS provides the prospective purchaser with answers to a lengthy battery of questions about the condition of the dwelling(s). The PCDS does nothing to relieve the buyer of the obligation to inspect and exercise due diligence. And, the seller is only charged with answering the questions on the PCDS to the best of their knowledge. One aspect of this requirement that many uninitiated buyers and sellers find surprising is that it is not unusual for sellers to voluntarily decline to provide the PCDS. In this case, the sole penalty is a $500 credit against the purchase price, payable to buyer only at closing. Whether or not to provide a PCDS is a decision made solely be the seller, with advice from their attorney and/or broker. Here again, local customs play a large role in the decision. Since the amount of $500 is uniform across the State, not surprisingly the PCDS credit is most often voluntarily given by sellers in New York City and other high value markets. Attorneys in these markets tend to believe that the $500 credit is a cheap form of insurance against possible later claims by an unhappy buyer, whether the seller had actual knowledge of some alleged defect or not. In rural parts of the State practices are more varied. It bears noting that there is a long list of exceptions when sellers are not required to give a PCDS or a $500 credit, such as at tax auctions or foreclosure sales.

The above is intended for general informational purposes and is not intended as nor should be taken as legal advice.